Trauma Does Not Exist: Why Your Past Doesn't Define You

Trauma affects far more people than we typically realize. Surprisingly, individuals with autism report PTSD rates of 32-45% resulting from perceived traumatic experiences, significantly higher than the general population's 4-4.5%. However, I believe that how we interpret and respond to trauma matters more than the events themselves.

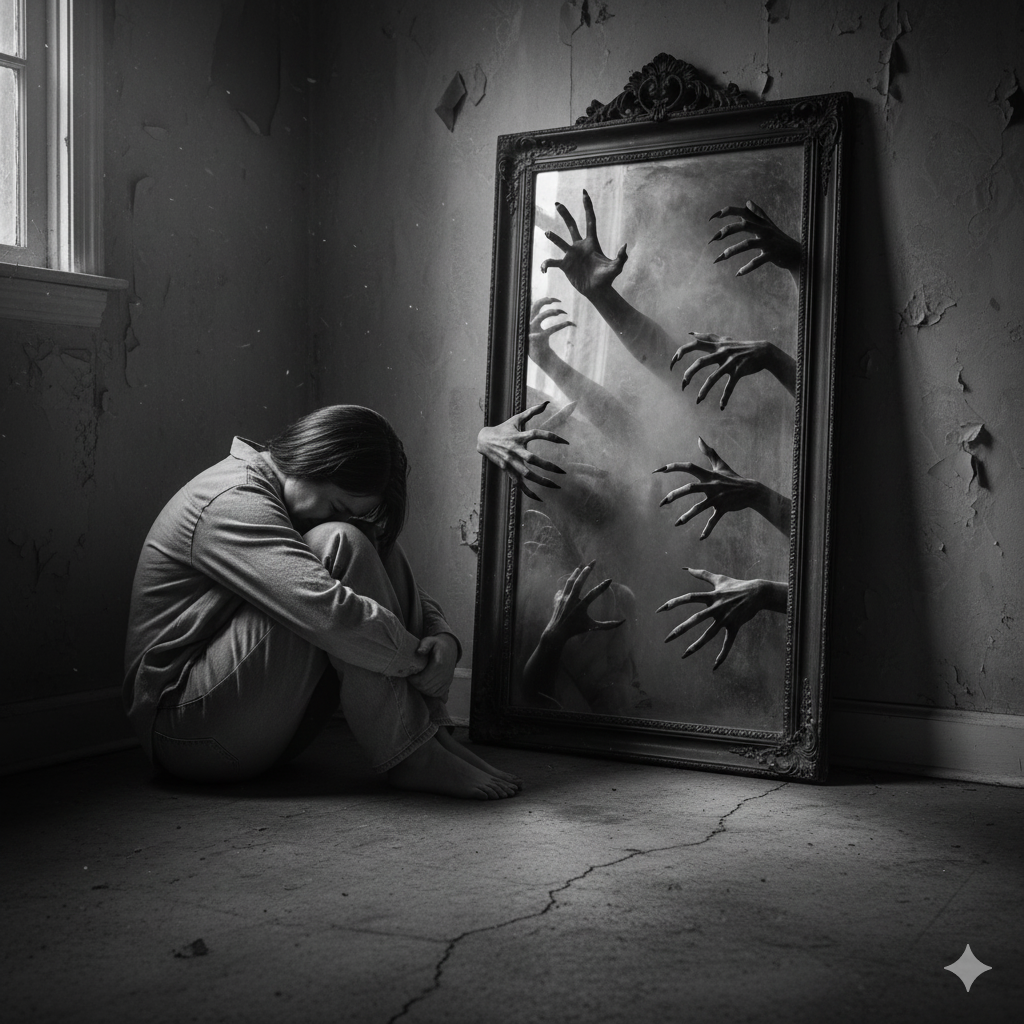

When trauma remains unresolved, it distorts our ability to interpret the world accurately. In fact, trauma can warp our perception of time, making past experiences feel present and creating cycles of emotional repetition. Despite these challenges, finding meaning after traumatic events is associated with post-traumatic growth. This raises important questions about trauma definition, how emotional trauma shapes us, and whether trauma is truly subjective.

In this article, we'll explore why your past doesn't define you, how childhood trauma influences your responses, and the path toward healing that goes beyond conventional trauma therapy approaches. I'll share insights into what posttraumatic growth looks like and how we can transform our relationship with difficult experiences.

What is trauma really?

For decades, mental health professionals have tried to pinpoint exactly what constitutes trauma. The American Psychological Association defines trauma as "any disturbing experience that results in significant fear, helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive feelings intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on attitudes, behavior, and functioning" [1]. Yet this clinical definition only tells part of the story.

Trauma definition vs trauma perception

The traditional view of trauma focused primarily on catastrophic events like war, natural disasters, or violent attacks. Today's understanding has evolved considerably. Trauma isn't defined by the event itself but by our individual experience of it. According to the Early Trauma Treatment Network, trauma occurs "when powerful and dangerous stimuli overwhelm the child's capacity to regulate emotions" [2].

This represents a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize trauma. Rather than categorizing certain experiences as inherently traumatic, modern perspectives recognize that trauma exists in our perception and physiological response. Essentially, trauma manifests as our mind and body's reaction to events that overwhelm our ability to cope effectively.

Furthermore, trauma alters how we process information. Unresolved trauma can create distortions in our perception, causing us to interpret neutral situations as threatening [3]. Our nervous system becomes primed to detect danger even in safe environments, leading to hypervigilance and mistrust.

Is trauma subjective?

The answer is unequivocally yes. Research consistently shows that identical events affect individuals differently, with only 3-10% of people developing post-traumatic stress disorder after traumatic experiences [4]. Additionally, according to the National Stressful Events Survey, lifetime prevalence for PTSD stands at 8.3% (DSM-5), though trauma exposure rates reach as high as 90% in the U.S. population [5].

What makes trauma profoundly subjective is how our unique history, biological makeup, and sociocultural context shape our response. Consequently, two people can experience the same event, yet only one may find it traumatizing. As noted in the trauma-informed care literature, "how an event affects an individual depends on many factors, including characteristics of the individual, the type and characteristics of the event(s), developmental processes, the meaning of the trauma, and sociocultural factors" [6].

The role of emotional trauma and sensitivity

Emotional responses to trauma vary dramatically between individuals, often appearing as anger, fear, sadness, or shame [6]. Some people struggle to identify these feelings, either because they lack familiarity with emotional expression or associate strong emotions with past trauma.

Notably, highly sensitive people (HSPs)—approximately 30% of the population—process traumatic events differently [7]. Their heightened nervous systems often experience trauma more intensely. "For sensitive people, the world can already be overstimulating. So when trauma occurs, it compounds the impact of the highly sensitive person's previously heightened nervous system" [7].

Research suggests that people with heightened sensitivity may develop post-traumatic stress symptoms from experiences that might not traumatize others. This doesn't minimize their suffering but acknowledges the remarkable diversity in how our bodies and minds process difficult experiences.

Rather than questioning whether someone's trauma "counts," I believe we should recognize that if their body shows trauma responses, then trauma is present. This validation opens the door to healing rather than perpetuating doubt about one's lived experience.

How childhood experiences shape trauma responses

Early experiences with caregivers profoundly shape our neural architecture, setting the foundation for how we respond to stress throughout life. Nearly 64% of adults in the United States have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) before age 18, while approximately 1 in 6 report experiencing four or more [8]. These statistics reveal how common childhood trauma truly is—and why understanding its impact matters so critically.

Attachment and early caregiver dynamics

Secure attachment, characterized by consistent support and emotional availability from caregivers, fosters emotional resilience that follows us into adulthood. This secure foundation improves stress management later in life while diminishing the likelihood of mental health disorders [9].

Conversely, trauma disrupts these crucial attachment patterns. Children develop distinct attachment styles based on caregiver reliability—secure, insecure avoidant, or insecure ambivalent/resistant [10]. When caregivers fail to provide predictable safety cues during the sensitive period of early development (birth to 24 months), it particularly impacts corticolimbic circuitry involved in emotion regulation [11].

Research demonstrates that early caregiving adversity often leads to accelerated maturation of the hippocampus and amygdala [11]. While this might initially appear advantageous, it ultimately shortens the period during which brain circuits remain plastic and receptive to positive influence. Studies show that exposure to childhood trauma, especially before age two, produces especially severe effects on neurodevelopment [11].

Signs of emotional trauma in adults

Adults who experienced childhood trauma often display distinctive patterns. Physical manifestations may include unexplained fatigue, difficulty sleeping, being easily startled, and changes in eating habits [12]. Emotionally, they might experience numbness, detachment, episodes of sadness, anger, or constant fear about the future [12].

Research has found that adults with four or more different ACEs face significantly higher risks for:

· Mental health issues including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and substance abuse [8]

· Physical health problems like heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes [8]

· Limited opportunities for education and stable employment [13]

These manifestations occur partially because childhood trauma alters brain regions involved in emotion regulation, memory, and stress response [9]. Conditions such as severe depression, borderline personality disorder, and dissociative disorders may all be exacerbated by these neurological changes [9].

Childhood trauma test: what it reveals

The ACE questionnaire has become a vital tool for understanding trauma's impact. It measures traumatic childhood events including abuse, neglect, and family dysfunction [14]. Particularly revealing is the "dose-response" relationship—as ACE scores increase, so does the risk for negative outcomes [15].

Studies show that children with high ACE scores (4 or more) demonstrated a 30-fold increase in learning or behavior problems compared to children with no ACEs [14]. Moreover, adults with high ACE scores were 12 times more likely to develop conditions like alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and depression [16].

Interestingly, research also indicates that having at least one supportive, trustworthy adult during childhood can mitigate these adverse effects [14]. This finding underscores how one reliable relationship can become a protective factor, even amid other significant adversities.

Why your past doesn't define your present

Many people believe their identities are permanently shaped by traumatic experiences. Yet research suggests a different narrative - one where trauma influences but doesn't dictate who we become. Understanding this distinction offers hope for those carrying emotional wounds from the past.

The myth of fixed identity

The concept of a permanent, unchangeable self doesn't hold up under scientific scrutiny. Our identities are remarkably fluid, constantly evolving through our social interactions and experiences. As Stanford research indicates, "the self is a social construction that is affected by the people you're interacting with and unfolding in relationships" [3].

This fluidity creates space for change and growth following trauma. Although childhood experiences significantly impact identity formation, they don't permanently cement who we are. Psychologist Erik Erikson recognized this when he identified eight stages of psychosocial development, suggesting that identity formation continues throughout life [17].

The illusion of permanence provides comfort—a stable sense of self anchors us in an unpredictable world. Nevertheless, recognizing identity as dynamic opens possibilities for redefining ourselves beyond trauma narratives.

How trauma responses evolve over time

Trauma responses naturally change as we heal and grow. For most survivors, symptoms gradually fade over days to months as they process difficult experiences [2]. This healing trajectory illustrates how our relationship with trauma shifts throughout life.

Resilience plays a crucial role in this evolution. Studies show that most trauma survivors develop appropriate coping strategies, including using social supports, to navigate aftermath effects [18]. Currently, research confirms that only a small percentage of people with trauma histories develop disorders meeting clinical criteria for trauma-related stress conditions [18].

The variability in trauma responses extends beyond initial reactions. Research demonstrates that traumatized individuals often display widely different symptoms that can change significantly within the same person over time [19]. This variability underscores how trauma responses aren't fixed but adapt as we heal and grow.

Posttraumatic growth definition and potential

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) represents positive psychological changes experienced through struggling with highly challenging circumstances [20]. Unlike resilience (returning to baseline), PTG involves profound transformation beyond recovery.

Researchers estimate that approximately 50-70% of trauma survivors experience some degree of posttraumatic growth [21]. This growth manifests across five key areas:

· Appreciation of life: Finding deeper meaning in everyday experiences

· Relationships with others: Developing stronger connections and empathy

· New possibilities: Discovering fresh paths and opportunities

· Personal strength: Recognizing inner resilience and capabilities

· Spiritual/philosophical change: Evolving beliefs and worldviews [20]

Importantly, growth doesn't eliminate suffering. PTG often coexists with distress and trauma-related symptoms [22]. In fact, some research suggests that the psychological struggle following trauma can be essential for growth to occur, as people reassess core beliefs and find new meaning [23].

This dual reality—suffering alongside growth—offers a more nuanced understanding of trauma's aftermath. It suggests that while trauma may always be part of our story, it needn't define our entire narrative or limit our potential for transformation.

The limits of behavioral therapy in trauma healing

Traditional behavioral therapies reveal significant limitations when addressing complex trauma healing. These approaches often focus on changing visible behaviors without necessarily addressing the deeper neurobiological impacts that trauma creates.

Why trauma responses are not just behaviors

Trauma-informed therapy represents a fundamental paradigm shift in treatment approaches. Instead of asking "What's wrong with you?", it asks "What happened to you?" - recognizing that trauma affects individuals far beyond their behaviors [24].

Trauma responses encompass complex physiological reactions that extend well beyond the commonly recognized fight, flight, freeze, or fawn categories. Researchers have identified additional responses including fright, flag, and faint [24]. These responses aren't simply behaviors to be modified; they represent the body's attempt to protect itself from perceived danger.

Our nervous systems can become dysregulated after trauma, making it difficult to manage emotional and physiological responses appropriately [24]. Even seemingly harmless triggers—a specific scent or tone of voice—can activate intense survival responses, leading to emotional turmoil and relationship difficulties.

Trauma code and the need for deeper understanding

Standard behavioral approaches often fail to decode what therapists call the "trauma code"—the unique way each person's body and mind store and respond to traumatic experiences. Since trauma impacts individuals physically, emotionally, socially, spiritually, and behaviorally [25], limiting treatment to behavioral modification misses crucial dimensions of healing.

Children prove particularly vulnerable to trauma's effects. Studies reveal that untreated childhood trauma worsens over time [26]. Yet conventional behavioral therapies frequently focus on symptom management without addressing the underlying neurobiological dysregulation.

When trauma therapy must go beyond CBT and ABA

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), among the most common trauma treatments, has notable limitations. The assumption that PTSD develops solely from dysregulated fear circuitry restricts CBT's effectiveness [27]. High negative affect—common in trauma survivors—disrupts cognitive processes necessary for CBT's success, including attention, processing, memory, and emotion regulation [27].

Similarly, Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) faces growing criticism from autism advocates who suggest it may inadvertently cause trauma [28]. One 2018 study indicated that ABA intervention during childhood correlated with the highest likelihood of PTSD symptoms among early childhood autism interventions surveyed [28].

More comprehensive approaches like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), somatic therapies, and psychodynamic approaches directly address both the physical and psychological dimensions of trauma, often proving more effective than behavior-focused treatments alone [6].

Healing through connection and meaning-making

Connection forms the foundation of effective trauma healing. Where traditional approaches sometimes fall short, relationship-based healing offers profound possibilities for those navigating trauma's aftermath.

The power of narrative and self-reflection

Narrative therapy helps trauma survivors make sense of overwhelming experiences by organizing memories into coherent stories. Through guided storytelling—whether verbal, written, or artistic—individuals transform jumbled, painful memories into manageable narratives [7]. This process reduces the emotional charge of traumatic memories while highlighting personal strengths and resilience [29].

When completing a trauma narrative, the story gets told repeatedly, allowing individuals to process their experiences within a broader context [30]. Research confirms that these controlled exposures help the brain properly store memories, diminishing their painful emotional impact [7].

Trauma therapy that focuses on relationships

Relationship-centered approaches recognize that "we are hardwired for connection" [31]. Trauma often disrupts our ability to trust and connect with others, yet healing occurs primarily within secure relationships [1].

For couples experiencing relationship trauma, therapeutic interventions first create space to explore individual attachment wounds—often unknown to the partners themselves [1]. Studies show that 60.89% of women who experienced relational betrayal met the criteria for PTSD [32], underscoring how profoundly relationship trauma affects mental health.

Rebuilding trust and emotional regulation

Trauma frequently disrupts emotional regulation, causing anxiety, depression, and interpersonal difficulties [31]. When trust is broken, our protective systems override connective ones, resulting in behaviors like criticism or withdrawal [31].

Effective therapy helps individuals identify triggers and develop coping strategies. This might involve practicing deep breathing or grounding techniques during stress [4]. Couples learn to express emotions and needs assertively while developing empathy for their partner's trauma responses [33].

Tools like EMDR and psychodynamic therapy

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) effectively treats PTSD by processing upsetting memories through bilateral stimulation [34]. Most people notice improvement after just a few sessions, with the full treatment typically lasting 1-3 months [34].

Psychodynamic therapy utilizes the therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for healing [35]. By bringing unconscious material to light, clients free themselves from patterns and impulses they previously couldn't articulate [35]. This approach enables "present-moment corrective interpersonal experiences" that occasion healing at both individual and relational levels [31].

Conclusion

Though trauma shapes many of our experiences, it doesn't have to define our identities or limit our futures. Throughout this exploration, we've seen how trauma exists primarily in our perception rather than in specific events themselves. The subjective nature of trauma explains why identical circumstances affect people differently, with some developing lasting symptoms while others quickly recover.

Childhood experiences undoubtedly create patterns that follow us into adulthood. These early foundations influence our attachment styles, emotional regulation, and stress responses. However, the myth of a fixed identity fails to acknowledge our remarkable capacity for change. Our neural pathways remain plastic, ready to forge new connections when given appropriate opportunities for healing.

Posttraumatic growth represents perhaps the most hopeful aspect of trauma recovery. This transformation goes beyond simply returning to baseline functioning. Instead, many survivors discover deeper appreciation for life, stronger relationships, and newfound personal strength after working through their traumatic experiences.

Traditional behavioral approaches often miss the mark because trauma lives in our bodies, not just our thoughts. Trauma responses represent complex physiological reactions rather than simple behaviors to modify. This reality explains why comprehensive healing approaches must address both physical and psychological dimensions of trauma.

Connection stands as the cornerstone of effective trauma recovery. Through narrative therapy, relationship-focused interventions, and specialized techniques like EMDR, people find pathways toward integration and wholeness. The healing journey requires patience, but meaningful relationships provide the secure foundation necessary for lasting change.

Your past experiences, while significant, need not dictate your future. The journey from trauma to growth remains uniquely yours, filled with possibilities for transformation beyond what you might currently imagine. The path forward involves acknowledging what happened without allowing those events to become your entire story. Most importantly, this healing journey reminds us that we are not our trauma—we are the resilience, growth, and wisdom that emerge as we move beyond it.

Key Takeaways

Understanding trauma's true nature and your capacity for healing can transform how you view your past and future potential.

• Trauma is subjective—your individual response matters more than the event itself, with only 3-10% developing PTSD after traumatic experiences.

• Your identity remains fluid throughout life; childhood experiences influence but don't permanently define who you become or can become.

• Posttraumatic growth affects 50-70% of survivors, creating positive transformation beyond simple recovery through deeper life appreciation and stronger relationships.

• Behavioral therapies alone miss trauma's neurobiological complexity; effective healing requires addressing both physical and psychological dimensions through connection-based approaches.

• Healing happens through secure relationships and meaning-making—your past experiences need not dictate your future story or limit your potential for growth.

The journey from trauma to transformation is uniquely yours, filled with possibilities for change that extend far beyond returning to your previous baseline functioning.

FAQs

Does trauma define who you are as a person?

While trauma can significantly impact your life, it does not have to define your entire identity. With proper support and healing, you can grow beyond your traumatic experiences and develop a more holistic sense of self.

How can someone begin to heal from childhood trauma?

Healing from childhood trauma often involves therapy, building a support network, practicing self-compassion, and gradually processing painful memories. It's a journey that takes time, but many people find that connection and meaning-making are crucial elements of recovery.

Can trauma responses change over time?

Yes, trauma responses can evolve. As you heal and grow, you may find that your reactions to triggers shift. This doesn't mean the trauma disappears, but rather that you develop new coping mechanisms and perspectives that allow you to navigate life more effectively.

What is posttraumatic growth?

Posttraumatic growth refers to positive psychological changes that some people experience after struggling with highly challenging life circumstances. This can include a greater appreciation for life, improved relationships, discovering new possibilities, increased personal strength, and spiritual or philosophical growth.

Are behavioral therapies alone sufficient for treating trauma?

While behavioral therapies can be helpful, they may not address all aspects of trauma. Comprehensive trauma treatment often requires approaches that consider both the psychological and physiological impacts of trauma, such as EMDR, somatic therapies, or psychodynamic approaches that focus on relationships and meaning-making.

References

[2] - https://www.helpguide.org/mental-health/ptsd-trauma/coping-with-emotional-and-psychological-trauma

[3] - https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/provocative-theory-identity-finds-there-no-you-self

[4] - https://woventraumatherapy.com/blog/trauma-informed-couples-therapy

[5] - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6544388/

[6] - https://www.laureltherapy.net/blog/evidence-based-practices-in-therapy

[7] - https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/narrative-therapy-for-trauma

[8] - https://pennstatehealthnews.org/2023/10/how-childhood-trauma-can-affect-health-for-a-lifetime/

[9] - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11077334/

[10] - https://teachtrauma.com/information-about-trauma/traumas-impact-on-attachment/

[11] - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8528226/

[12] - https://newdirectionspgh.com/counseling-blog/common-signs-of-emotional-trauma-in-adults/

[13] - https://www.utmb.edu/pedi/categories-tags/2021/04/07/toxic-stress-and-the-long-term-effects

[14] - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8882933/

[15] - https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

[16] - https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/24875-adverse-childhood-experiences-ace

[17] - https://www.harleytherapy.co.uk/counseling/who-am-i-identity-crisis.htm

[18] - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/

[19] - https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0149763413001590

[20] - https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/11/growth-trauma

[21] - https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/post-traumatic-growth

[22] - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-traumatic_growth

[23] - https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220311-the-complicated-truth-of-post-traumatic-growth

[24] - https://positivepsychology.com/trauma-informed-therapy/

[26] - https://stanmed.stanford.edu/beyond-behavior/

[27] - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27301345/

[28] - https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/is-aba-therapy-harmful

[29] - https://www.integratetherapyandwellness.com/blog/reflective-healing-through-a-trauma-informed-lens

[30] - https://www.therapistaid.com/therapy-guide/trauma-narratives

[31] - https://www.nbcc.org/resources/nccs/newsletter/building-trust-after-trauma

[33] - https://dbtofsouthjersey.com/which-therapy-is-best-for-relationship-trauma/